There’s something incredibly powerful in the simple idea of being with someone. Not doing to or even doing with or for, but truly being with. For people with Profound and Multiple Learning Disabilities (PMLD), attunement, emotional connection, and flexible shared time can help to create more space for trust and support wellbeing.

This beautiful video series by Joanna Grace, “New to Profound Teaching,” captures the need for us to have a deep respect for the humanity of every person, and is a call to slow down, tune in, and listen, not just with our ears, but with our bodies, instincts, and to give ourselves and those we support more expansive time.

As Nind & Grace (2024) argue, emotional wellbeing in educational and care settings for those with PMLD is something that is shared and built in relationship. This means the wellbeing of practitioners and students is deeply connected, emerging through relational moments of presence and mutual recognition. Having an awareness and understanding that those with PMLD may experience time differently is important when building relationships.

Nind and Grace’s paper calls for a ‘greater attention to empathising in embodied, perceptual ways to aid mutual understanding and support wellbeing’ understanding differences of experiencing time is part of supporting people’s emotional wellbeing‘. Being rushed and the needs of those with PMLD being invalidated due to time pressure we may feel as practitioners is not helpful for anyone, we need to slow down, tune in and perhaps let go of some of the expectations we have for ourselves as practitioners to create more meaningful moments together with those we are supporting.

Attunement and Shared Embodied Presence

Being with someone means sharing time and space in a way that honours their authentic needs, valuing presence, all ways of communicating, and pace. For people with PMLD, this often looks like us having an attunement to the smallest signals that they may express, breath, body movement, vocalisations, eye gaze, muscle tone and different vocalisations. These embodied expressions are communication.

When we slow down enough to really notice and respond, we build trust and safety. It’s in these shared, co-regulated moments that connection happens. There’s no expectation of “output,” or “outcome”, just a deep respect for what it means to be together and the outcome that may evolve from that connection. Nind & Grace (2024) describe these moments as emotionally co-regulated spaces. This is where both practitioner and student can engage in a dynamic, reciprocal dance of attunement so emotional wellbeing is not only supported for the student but with them, in a shared presence.

Believing Instincts, Honouring Families

Families and close carers are often the most finely tuned communicative partners for someone with PMLD. Their knowledge, instincts, and insights must be centred and believed by teachers. Validating parent/carer knowledge and also their trauma is important as so many have likely been dismissed or disbelieved when they’ve noticed something others didn’t see.

Creating a network of care around the person that honours this understanding and connection isn’t just good practice, it’s essential to provide meaningful support and co-regulation and a way of discovering more about those we are supporting.

Letting Go of Rigid Time

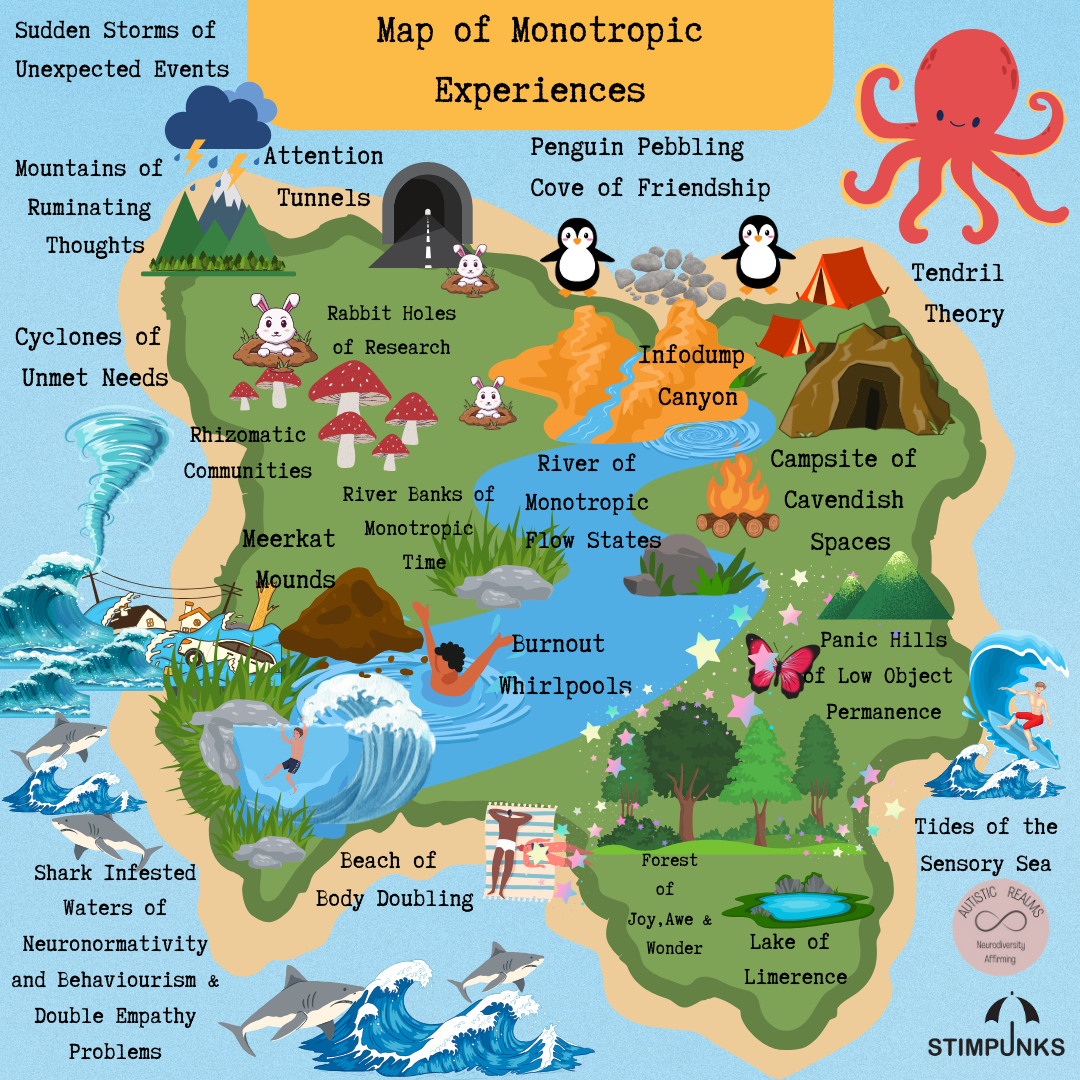

I have written quite extensively over the past few months about the importance of understanding how neurodivergent people, especially Autistic/ ADHD people may experience time in a different way to neurotypical expectations. Time is often felt different, it may spiral, loop, stretch, stall and flow depending on energy and monotropic attentional resources and affects how we navigate life and also experience and recall memories.

Differences in time perception is not limited to Autistic or neurodivergent people it is likely to be felt differently for anyone who is disabled, chronically ill and has a different way of experiencing the world. Considering differences of time perception may be even more significant for those supporting people with PMLD.

By rethinking our relationship with time we can shift the narrative that there is a right way to be, a right way to feel and respond and navigate time. So much of education and care is structured around doing: fitting tasks into schedules, completing plans, ticking boxes, however people with PMLD may experience time very differently to their carers. Processing may be slower, more embodied, more of a felt sensory experience, engagement may look like stillness and a quiet presence.

We need to honour the different experiences of time for those we are supporting, not impose our standards and expectations of time. As teachers/ carers we need to consider letting go of the urge to press ahead just because the resources are ready or the timetable says it’s time to move on. We need to give ourselves permission to stop, pause, or abandon our lessons plan entirely. By tuning into students more, we can build trust so we can be more responsive and change plans in the moment to expand the time they may need.

Nind & Grace (2024) remind us that rigid demands and performative pressures can erode emotional safety in educational spaces, not only for students, but also for staff. A relational, flexible approach can reduce emotional labour by allowing space for attunement rather than compliance.

Curriculums, sensory activities, and teaching goals should be flexible tools, not rigid scripts, timetables could be re-imagined as flexible routines rather than strict schedules. This not only provides more space for learners needs to be accounted for, it also lifts the pressure for teachers to only feel they are working in the classroom if every child is on task at all times. When we are working with those with PMLD our expectations of what being engaged and what learning looks like is different and rest, recovery and processing time needs to be taken into account and is just as meaningful (if not more meaningful) as the planned lesson. The only real non-negotiables in a school day are often personal hygiene needs, feeds, medication, and essential positioning/ensuring people are as comfortable as possible, everything else can adapt around the person’s needs and interests and how much time they may need.

‘Relational Empathy’

By having a more flexible approach to time and what we think of as important we can create more space for really being with people, creating safety, comfort, tuning in and bridge the double empathy gap (Milton, 2012). A short planned 10 minute activity may expand into an hours session or full lesson may need to stop before it has even really started. When we tune in we can gauge people’s energy and needs, this echoes what Nind & Grace (2024) highlight about the importance of empathy being a relational issue, ‘it is not about ‘feeling the same, but instead involves ‘feeling into’, that is, ‘grasping another’s feelings’. There is emotional connection when we engage using this kind of empathy – an affective response because we are ‘emotionally available and relatable.………..Creating ‘a relational space of ‘being with’ between care recipient and provider – an unrushed moment of meaningful encounter (Cranford and Miller, 2013)’ (Hall and Wilton 2017, 734) becomes possible.’

Less is More: The Power of Rest and Recovery

In classrooms or care settings, there can be pressure for staff to look busy or “on task” all the time, however real engagement often happens in the in-between spaces: in the pause, in the rest, in the quiet connection and in those unexpected moments between activities, in transitions and even during care routines.

People with PMLD often need far more rest, recovery, and processing time than we might assume. These moments are not time out of learning; they are valuable moments where learning, connections and processing can take place in their own way. Nind & Grace (2024) highlight that wellbeing often arises in these quiet, seemingly “unproductive” moments, what they call “affective encounters” that foster security, mutual regulation, and relational warmth. These moments matter as much, or may be more than formal learning outcomes. They are what gives meaning to life, capturing the moments of shared joy, the magical glimmers, the moments of presence that can’t really be captured on video, in a written observation, the moments where there isn’t a target or goal but there is something felt between two people that is meaningful and enriches the day.

We need to embed more moments of pause into the rhythms of our days and allow time to expand when needed as led by the person we are supporting. It isn’t about doing less care or less teaching; it’s about teaching and being with people in a more meaningful way that honours their needs and time.

Staying Curious, Assuming Personhood

I loved Joanna’s reminder in her video from the series New to Profound Teaching about not assuming competence or incompetence, instead we need to assume personhood. We need to stay curious and be open and flexible and recognise that time may not be linear and that our 24 hour clock and busy timetable is unlikely to have any meaning for a person with PMLD. Their time is in the moment, it is sensory and felt and embodied in their personhood.

Some days, a person might be alert and engaged, other days, they may not seem to respond but this doesn’t mean they aren’t present. It might mean they’re tired, unwell, or just processing the world differently, engagement with everyone fluctuates depending on their environment and energy and for those with PMLD this is likely to be felt more intensely. When we honour these differences without judgement we are showing that we care and can be trusted. Having a meaningful trusted relationship is the foundation for safety and learning.

Slowing Down to Connect & Expanding Time

Supporting someone with PMLD means stepping into a different rhythm and temporality, shaped by relational attunement, respect, trust and a deep understanding of sensory differences. We need to give ourselves and those we are supporting more time to experience, more time to notice, more time to respond, more time to rest and process and also more time to simply be with themselves and with others without any fixed goals or agenda.

When we prioritise presence over performance, relationship over routine, and connection over control, we begin to resist the dominant, productivity-driven models of time that so often shape care and education. People with PMLD may experience and express time in more diverse, embodied, and relational ways, often in direct opposition to the rigid, linear, and fast-paced norms imposed by school timetables and care settings.

By letting go of fixed expectations and embracing more flexible, attuned approaches to an individual’s daily rhythms, we can create space for people with PMLD to build trust, experience safety, and engage on their own terms. A relational, flexible approach to time enables more meaningful interactions, reduces stress, burnout and honours the rich, sensory, and interconnected ways that people with PMLD experience the world.

As Nind & Grace (2024) affirm, the emotional wellbeing of people with profound intellectual disabilities is built through ethical, responsive relationships, ones grounded in presence, patience, and co-regulated emotional rhythms. This way of working requires us to be with, not just do for. In slowing down, tuning in, and making room for multiple ways of being and knowing, we can co-create moments of shared presence which is so valuable and can bring so much meaning to life. Time is not something to manage, it can become something we can share together.

References:

Cranford, Cynthia J, and and Diana Miller. 2013. “Emotion Management from the Client’s Perspective: The Case of Personal Home Care.” Work, Employment and Society 27 (5): 785–801. Crossref. Web of Science.

Hall, E., and R. Wilton. 2017. “Towards a Relational Geography of Disability.” Progress in Human Geography 41 (6): 727–744. Crossref. Web of Science.

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: the ‘double empathy problem.’ Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Nind, M., & Grace, J. (2024). The emotional wellbeing of students with profound intellectual disabilities and those who work with them: a relational reading. Disability & Society, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2024.2407819

New to Profound Teaching ,Youtube series by Joanna Grace (2025)