This short blog gives an overview of my personal insight into monotropism and polytropism. If you’d like to explore the research and gain deeper knowledge, click here

Monotropism (Murray et al., 2005) is a cognitive style associated with Autistic experiences in which more attentional resources are channelled into fewer areas at any one time, enabling sustained focus, deep focus, connected thinking, and meaningful sensory experiences. The theory of monotropism helps to reframe the previous deficit based understanding of Autism into a strength based neuro-affirming framework that honours our natural flow (Heasman et al., 2024).

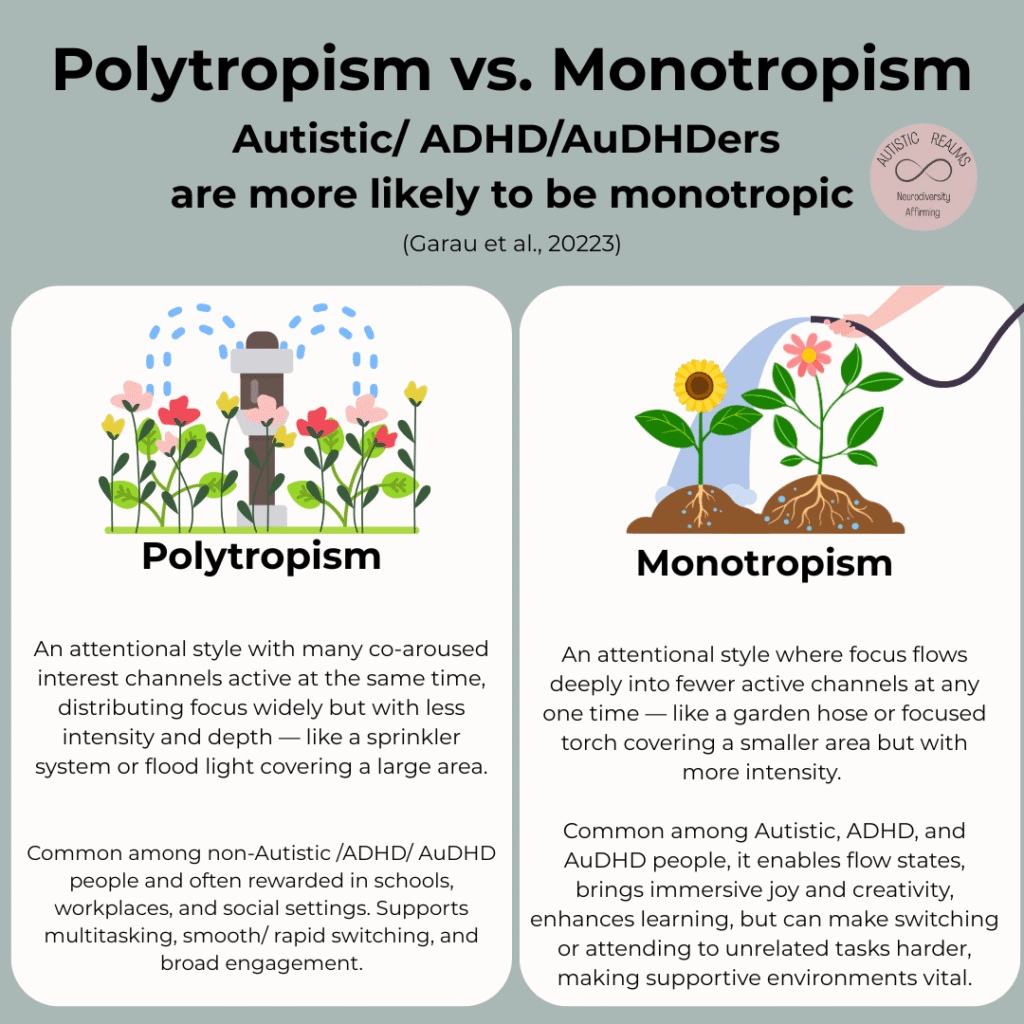

Polytropism, more commonly associated with being non-Autistic or non-ADHD/AuDHD, involves holding many active interest channels open at once, with attention spreading more evenly across everything. Fergus Murray likens the polytropic attentional style to a sprinkler system, where the same limited supply of attention is dispersed over a wide area. This style supports flexibility and allows for smoother, faster switching between tasks or topics, but often at the cost of less depth. They liken monotropic attentional styles to being more like a focused torch beam, tap, or hosepipe, where attentional resources are concentrated into the flow, enabling greater depth of thinking and richer experiences but at the cost of reduced capacity for task switching and maintaining multiple active channels at once.

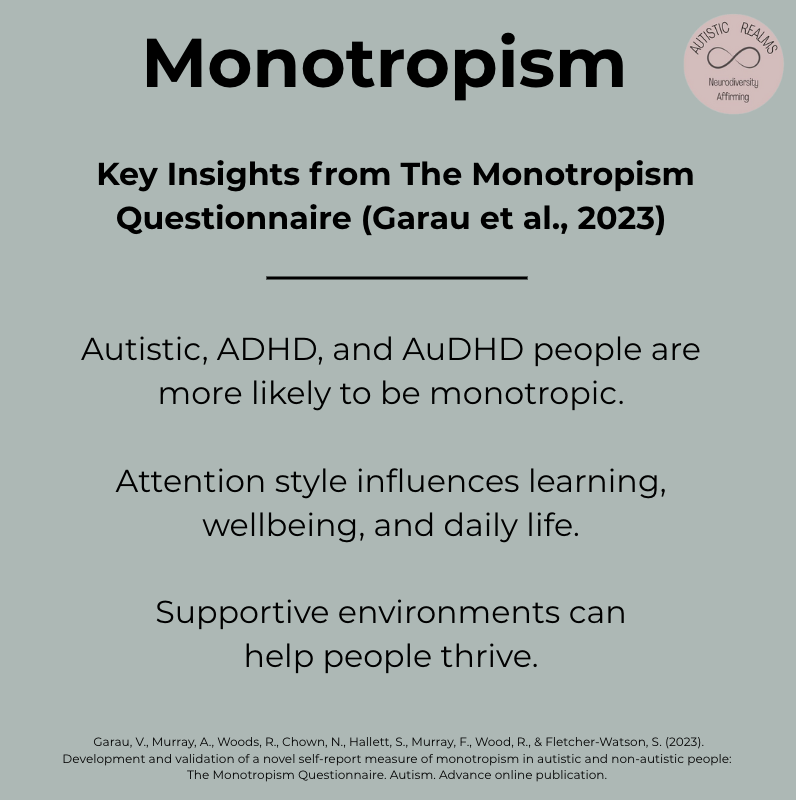

The Monotropism Questionnaire (MQ) is a research tool designed to measure monotropic traits by Garau et al. (2023). They found that ADHDers — and especially AuDHDers — scored significantly higher on the MQ than non-Autistic people, indicating a strong overlap between Autism, ADHD, AuDHD, and monotropic attention.

Both monotropism and polytropism have strengths and challenges, but most environments are built with polytropism in mind, which is society’s neurotypical default. Understanding these differences helps us design spaces and support systems where everyone can thrive and where attention is valued as a natural variation, not a flaw.

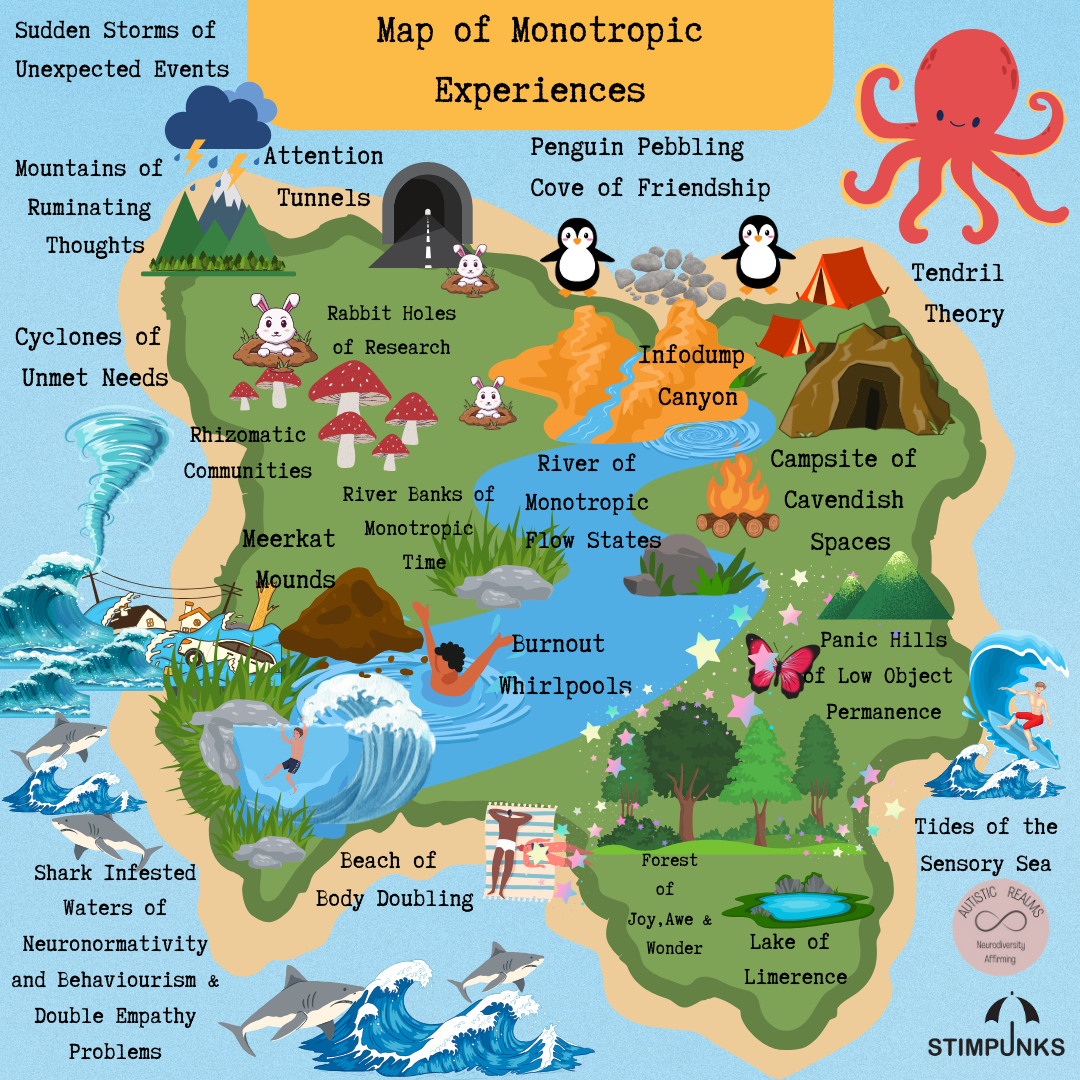

When an interest aligns, monotropic attention often focuses into a single activity, idea, experience or line of thought. However, (for me at least!) this focus isn’t rigid as is so often perceived from the outside, it can expand organically into related topics or experiences, forming intricate webs of understanding. Monotropism can generate immersive sensory experiences and complex, constellation-like or rhizomatic thought patterns, where one idea, experience or event naturally flows into another.

Monotropism To be monotropic is to concentrate more attentional resources into fewer channels at anyone time, enabling sustained engagement, flow and deep connections between ideas or experiences.

Polytropism: To be polytropic is to have many interests active simultaneously, with attention shared more evenly across different channels, supporting flexible switching and smoother and easier parallel processing.

Polytropism supports flexibility, rapid and smoother adaptation, juggling multiple streams of information at once — traits well-suited to environments that demand constant responsiveness such as busy classrooms and work places and joining in social occasions. Monotropism allows for depth, sustained flow, and nuanced connection-making — but can make task-switching and multiple channel processing harder, particularly when pulled away from something meaningful or forced to divide focus between tasks/ input and stimuli.

In overstimulating or unsafe environments, people with monotropic attentional styles may experience exhaustion or burnout when pressured to split focus across too many competing demands. However, in environments that honour monotropism and organic monotropic ways of being through uninterrupted time, minimal distractions, and encouragement to follow interests in depth — monotropism becomes a powerful driver of creativity, learning and meaning making.

Understanding these differences is key because many schools, workplaces, and social systems are built with polytropic attentional patterns in mind. Expectations to multi-task, respond instantly, or split focus can lead to misunderstandings, with monotropic individuals unfairly labelled as being rigid, obsessive, inattentive or disorganised. Recognising these as attentional differences due to environmental factors rather than deficits opens the door to better support, accommodations, and self-advocacy.

The theory of monotropism doesn’t just explain how we pay attention — being monotropic shapes how we experience, interpret, and connect with the world. By understanding and valuing both monotropic and polytropic styles, we can create environments where everyone can thrive, and where differences in attention and flow are seen as natural variations in human attention, not problems to be fixed.

References

Garau, V., Murray, A., Woods, R., Chown, N., Hallett, S., Murray, F., Wood, R., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2023). Development and validation of a novel self-report measure of monotropism in autistic and non-autistic people: The Monotropism Questionnaire. Autism. Advance online publication. https://osf.io/preprints/osf/ft73y

Heasman, B. (2024). Towards autistic flow theory: A non‐pathologising conceptual approach. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 54(4), 623–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12445

Murray, D., Lesser, M., & Lawson, W. (2005). Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for autism. Autism, 9(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361305051398

Check out: www.monotropism.org