Your basket is currently empty!

Monotropism vs Polytropism: ADHD, AuDHD & Autistic Attention

The Myth of the “Polytropic ADHD/AuDHD Mind“

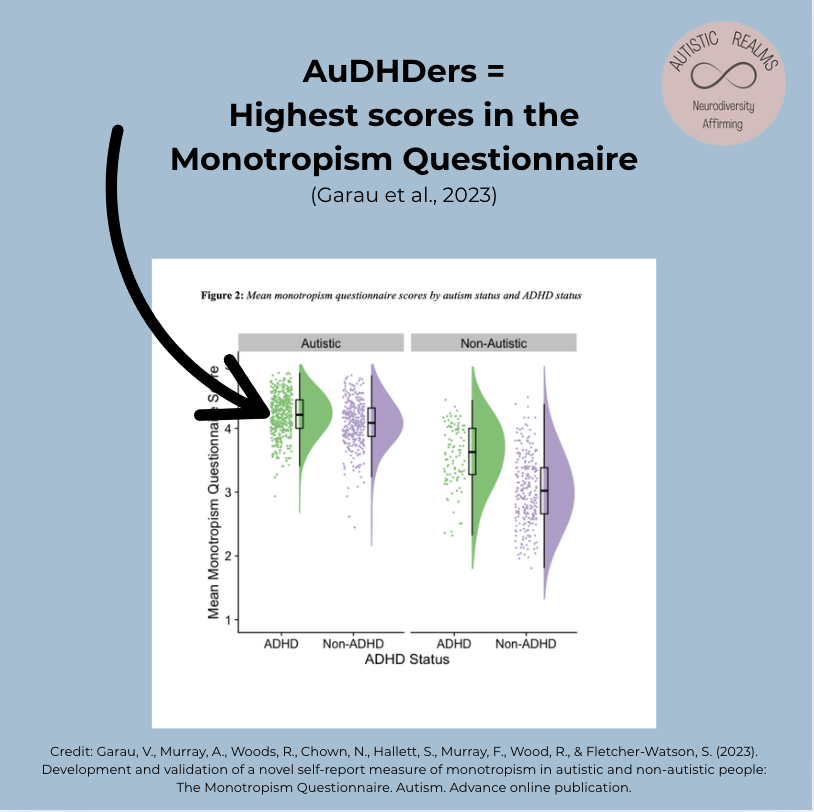

While monotropism is most often linked to Autistic experience, research from Garau et al. (2023) in the Monotropism Questionnaire (MQ) shows monotropism is especially resonant amongst ADHDers, particularly those who are AuDHD. A common myth about being ADHD or AuDHD is that it means having a “polytropic” mind — a brain that’s constantly jumping between lots of interests and stimuli, switching tasks easily (or, in deficit-based views, being constantly distracted and dysregulated). This stereotype is baked into educational policies, clinical descriptions, and workplace assumptions. It underpins the belief that ADHDers and those of us who are both Autistic and ADHD (AuDHD) are naturally scattered, unable to sustain deep focus.

This myth is not only oversimplified, but I think it is actively harmful. It sets up expectations that clash with the lived experiences of many monotropic (Autistic/ ADHD/ AuDHD) people, leading to misunderstandings, lack of meaningful accommodations, and potential burnout.

Research and lived experience show that many ADHDers, especially AuDHDers, have attention styles that are the opposite of being polytropic and are in fact often intensely monotropic. ADHD and AuDHD people are more likely to resonate with the theory of monotropism, a cognitive style common among Autistic people, where attention flows deeply into a small number of highly aroused interests at any one time.

This article draws together empirical findings, lived experience, and theoretical frameworks to challenge the myth that ADHDers and AuDHDers are “naturally polytropic”, a conversation that I frequently have to dispel. By grounding our understanding of Autistic/ ADHD/ AuDHD experiences in the theory of monotropism, we can reframe what it means to support monotropic people not as having scattered or obsessional attention that needs to be “fixed,” but as monotropic people who have deep, interest-based systems that need to be respected and protected.

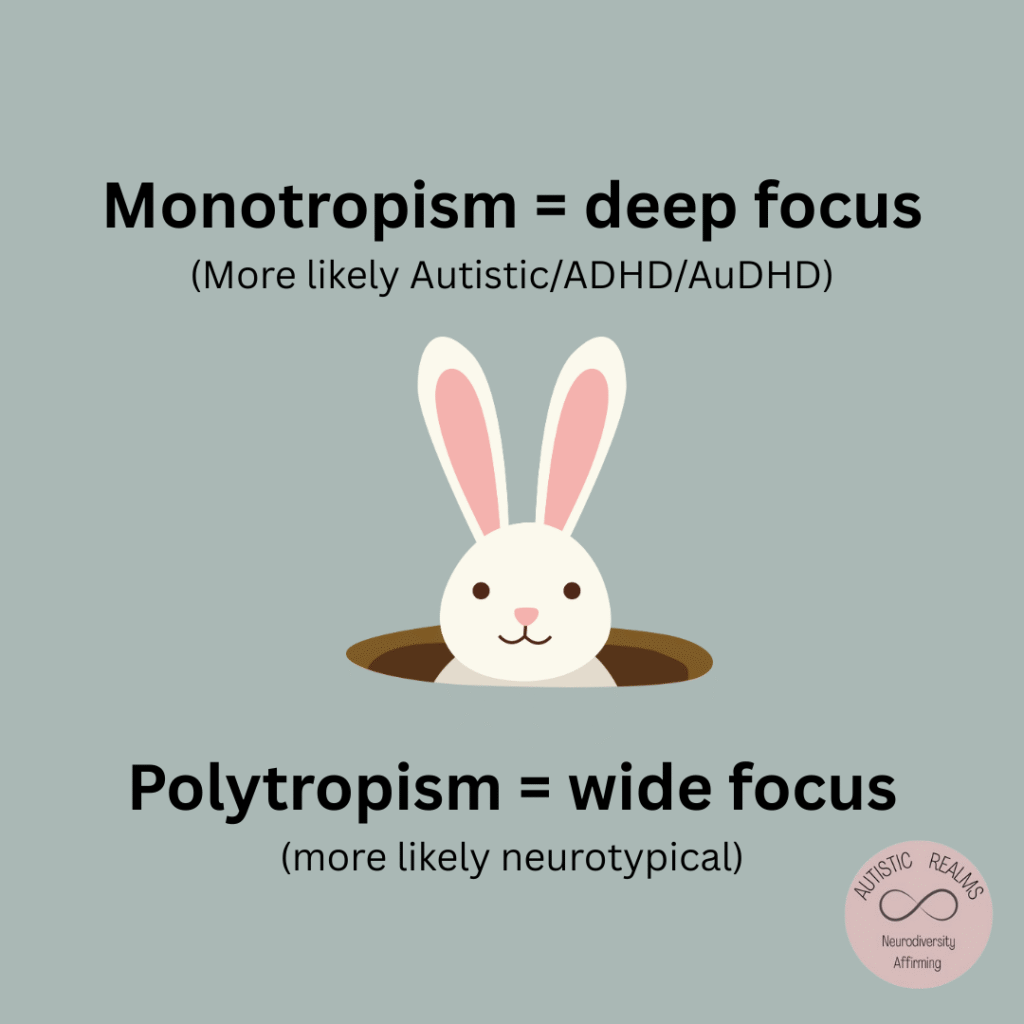

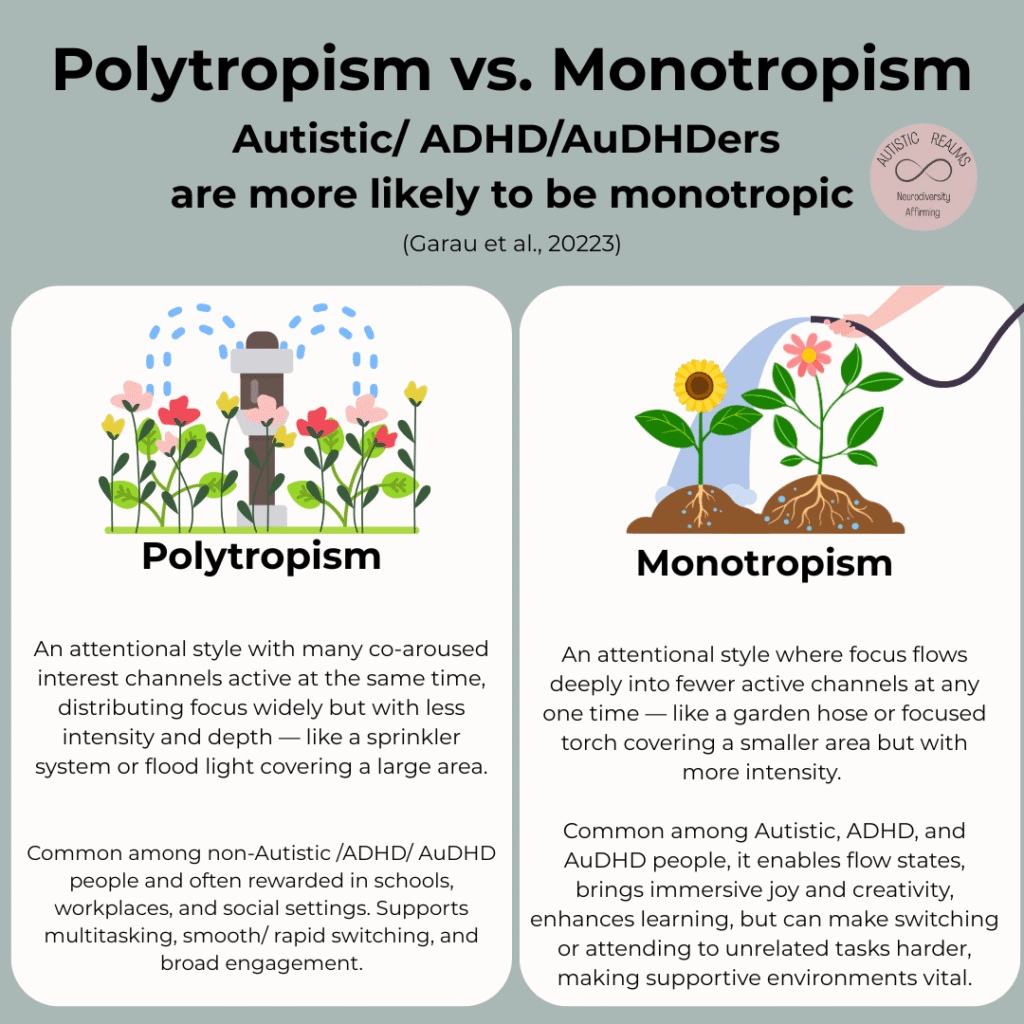

Polytropism vs. Monotropism

Polytropism (wide focus)

To be polytropic is to have many interests active at the same time, with attentional resources spread more broadly across them. Fergus Murray likens polytropism to a sprinkler system where the same limited supply of attention is dispersed over a wide area, allowing many things to receive some focus at once with equal effort.

Polytropism is the neuronormative default for most non-Autistic/ ADHD/AuDHD people, and it is the attention style that education systems, workplaces, and many social environments are built around. It honours:

- Rapid switching between tasks/ events

- Multitasking, juggling and filtering multiple inputs at once

- Sustaining moderate attention on a broader range of topics / sensory experiences at the same time

- Supports typical neuronormative conversation and socialising skills

This style is not inherently “better” or “worse” than being monotropic, but it is the model most often rewarded in school systems and workplace environments. For monotropic people, this cultural bias can mean constant pressure to function and mask in a way that’s misaligned with how our monotropic attention naturally flows.

Monotropism (deep focus)

Monotropism is a theory developed in the late 1990s by Autistic researchers Dinah Murray, Mike Lesser, and Wenn Lawson. It describes the tendency for our attention to be drawn deeply into a few highly engaging interests at any given time. The theory was presented in their 2005 research paper Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for autism.

If polytropism is like a sprinkler system or a wide flood light, monotropism is more like a garden hose or a focused LED torch. If you are monotropic the same limited attention flows into fewer channels but with far more depth and intensity. These “attention tunnels” can bring immersive joy, creativity, and hyper focus, but they also mean it is harder to notice or respond to things outside that tunnel.

Murray et al. (2005) describe attention as a finite resource. For monotropic people:

- Fewer interests are engaged at any given time, but each receives higher-intensity focus.

- Deep engagement may mean losing track of time, missing background / sensory or emotional cues, or finding interruptions distressing.

- Social interaction, task-switching, and fast-paced conversation can be more demanding, not because of a lack of ability, but because they require broad attention distribution.

Importantly:

- Monotropism is interest-based — “interest” meaning anything that commands attention, not just hobbies or ‘special interests’.

- An active interest carries sensory, emotional, and motivational energy, making it easier to stay engaged with related tasks.

- Tasks outside that focus can feel irrelevant or overwhelming and be hard to navigate.

While monotropism is most often linked to Autistic experience, research from Garau et al. (2023) in the Monotropism Questionnaire (MQ) shows monotropism is especially resonant amongst ADHDers, particularly those who are AuDHD. This challenges the stereotype that ADHDers are inherently “scattered” or “polytropic” and affirms that ADHDers and AuDHDers are statistically more likely than other groups to score highly on the MQ and relate to the theory of monotropism.

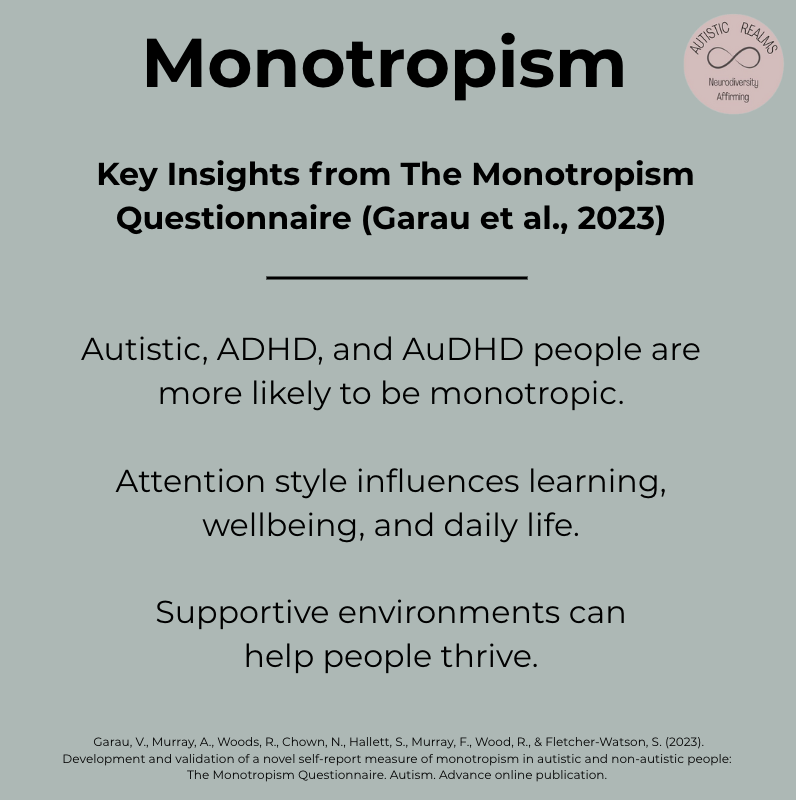

What Research Shows

The Monotropism Questionnaire (MQ) was co-produced with an Autistic-led group to make sure it reflected how monotropism actually feels from the inside, not just how it looks from the outside.

For many years, monotropism was understood mainly through lived experience and theory (Murray et al., 2005; Milton, 2014). While it resonated strongly with Autistic people, there had been little formal reseach across wider communities and fields. That changed with the Monotropism Questionnaire as it was the first large-scale, community-informed tool to measure monotropism in both Autistic and non-Autistic people, including ADHDers and AuDHDers. More information about how this theory went viral after the MQ was published check out my blog Monotropism Questionnaire: Inner Autistic and ADHD Experiences (2023).

- AuDHDers generally scored the highest in the MQ.

- Autistic people not identifying with ADHD scored the second highest in the MQ.

- ADHDers who were not diagnosed or did not identify as Autistic still tended to score higher in the MQ than non-Autistic participants.

- Monotropism is not rare — it exists across the whole population, but traits are more intense and far more common among Autistic people, ADHDers, and especially AuDHDers.

This evidence challenges the assumption that ADHD automatically means being “polytropic”. Many ADHDers and AuDHDers experience life monotropically, through depth, immersion, and intensity.

Links with other research

The MQ findings align with earlier studies showing that Autistic people often:

- Have reduced ability to process multiple sensory channels at the same time (Goldstein et al., 2001; Collignon et al., 2013)

- Experience strong emotional reactions to interruptions (Ozsivadijan et al., 2021)

These are not signs of “poor attention control.” They are natural consequences of a deep-focus attentional style prioritising depth over breadth.

The Eight Factors of Monotropism

The MQ identified eight main themes that describe monotropic experience:

- Special Interests – Deep, lasting passions that may fluctuate or last for years or even a lifetime.

- Rumination and Anxiety – Loops of thought or worry about uncertainty.

- Need for Routines – Stability is needed for protection against overload.

- Environmental Impact on the Attention Tunnel – Predictability and sensory safety help sustain focus; disruption makes switching harder.

- Losing Track of Other Needs During Focus – Forgetting to eat, drink, or rest while engaged (I think this is likely linked to the interoception system)

- Struggle with Decision-Making – Especially when the choice is not linked to an active interest.

- Anxiety-Reducing Effect of Special Interests – Using passions to regulate the sensory system, emotions, and recover from stress.

- Managing Social Interactions – Finding it hard to track group conversations or switch between social and non-social attention.

This research confirms what many monotropic people, Autistic or otherwise, have been saying for many years in our community:

- Deep-focused attention is not a deficit.

- It brings unique strengths and also specific needs.

- Understanding monotropism is essential to reducing burnout and increasing well-being.

Hyperfocus and Flow in Monotropic ADHD/AuDHD People

Our society which is based on neuronormative ideals and expectations and popular mainstream ideas about ADHD often focus on our fragmented attention. There is the belief that if you’re ADHD it means you are constantly jumping to the next thing, being easily distracted, and being unable to hold focus for long. While distractibility can be part of ADHD, this is only one side of the story and is likely due to unmet needs and an unsupportive environment.

Monotropism does not simply mean focusing on one thing, it means concentrating more attentional resources into fewer channels, enabling hyperfocus and richly connected experiences. Many ADHDers, and perhaps especially AuDHDers, when in safe environments and with needs met, experience periods of intense, sustained focus when an interest aligns and we enter flow. In these moments, attention often narrows into a single activity, idea, or interest for hours at a time, yet it rarely stays fixed (at least for me!). It can branch organically into many related interests and experiences, expanding outward in a deep, interconnected way. This is not a deficit — it can generate immersive sensory experiences and complex, constellation-like or rhizomatic thought patterns, where one idea or moment naturally leads to another.

ADHD & Hyperfocus

Hupfeld et al. (2019) describe hyperfocus as:

“A state of heightened, intense focus… timelessness, failure to attend to the world, ignoring personal needs, difficulty stopping and switching tasks, feelings of total engrossment in the task, and feeling ‘stuck’ on small details.”

This is almost identical to what monotropism theory calls an attention tunnel (Murray et al., 2005), a deep, narrowed channel of awareness focused on one or two things, with everything else outside that tunnel fading from perception. The seems to be many parallels:

- Fewer interests are active at the same time

- High-intensity engagement

- Difficulty switching tasks

- A narrowed but deep sensory and cognitive field

Similarly, Ashinoff and Abu-Akel (2021) call hyperfocus the “forgotten frontier of attention,” a state where engagement becomes so complete that other stimuli disappear entirely.

Flow & Wellbeing

Grotewiel et al. (2022) found that ADHDers reported more experiences of hyperfocus than their non-ADHD peers, but scored lower on some aspects of flow, suggesting hyperfocus can be a kind of deep flow state. It can be energising and productive, but isolating and risky for people’s well being when it means neglecting basic needs or relationships.

More recently, Heasman’s (2024) Autistic Flow Theory has expanded this understanding of flow and attentional resourcing by offering a non-pathologising, Autistic-led framework for this deep focus many of us monotropic people experience. This theory explains how and when flow emerges and why it matters for our wellbeing. Flow, in this context, is not simply a performance boost or a productivity tool; it is an intrinsically rewarding state where attention, motivation, and sensory environment align. For monotropic people, they suggest flow emerges most easily when three conditions are met:

- Interest-based engagement — the activity has personal meaning and emotional resonance.

- Sensory and environmental safety — surroundings are predictable and comfortable, reducing the need for constant vigilance

- Freedom from unnecessary interruption — sustained time without forced switching or competing demands

Heasman reframes flow as an essential part of Autistic and monotropic wellbeing, not an occasional “bonus” state. This matches Garau et al.’s (2023) Monotropism Questionnaire findings, where factors such as environmental impact on the attention tunnel and losing track of other factors during focus show that the same deep engagement that fuels creativity and learning can also be disrupted or supported by the surrounding ecology and our environments.

Interest-based attention, not a deficit

Bertilsdotter Rosqvist et al. (2023) describe ADHD attention as variable and interest-based, supporting the idea that it’s not about being “good” or “bad” at paying attention but more about whether the activity is meaningful to the person. They describe hyperfocus as a joyful flow state where you have full absorption in something that matters to you.

This is exactly in line with monotropism’s non-pathologising view – deep, narrow attention is not a problem to fix, it is a way of thinking and processing that can bring creativity, depth, and focus, but can also leave us vulnerable in environments that do not meet our needs.

Embracing Monotropism: Dispelling Myths About ADHD, AuDHD, and Polytropism

Below are some of the most persistent myths that I regularly encounter on social media and in various communities I engage with. These are just my own experiences and thoughts and are by no means extensive.

Myth: ADHD / AuDHD = distractibility and polytropic thinking.

Truth: ADHDers and AuDHDers scored highly on the monotropism questionnaire and are more likely to be deeply monotropic

Myth: Monotropism is only “an Autistic thing.”

Truth: Monotropism is a theory that covers a spectrum of experiences with AuDHDers, Autistic people and ADHDers scoring higher in the monotropism questionnaire than other cohorts.

Myth: If we are not visibly busy, we are doing nothing.

Truth: Deep-focus engagement can be invisible to outsiders. Monotropic focus often happens quietly and internally, making it easy for others to misinterpret it as avoidance or lack of productivity.

Myth: AuDHers/ ADHDers work best in high-switch, high-stimulus, chaotic environments.

Truth: The “thrives in chaos” stereotype harms ADHDers and AuDHDers. This shifts responsibility away from the environment, normalising the mismatch and potentially fuelling burnout cycles (Hossain & Bain, 2025; Raymaker et al., 2020). Chaos is likely due to unmet needs and overloading capacity.

Monotropism offers a powerful lens for rethinking how we understand Autistic, ADHD, and AuDHD attention. By moving away from deficit-based theory, dispelling myths and recognising monotropism as a valid cognitive style, we can build environments that protect deep monotropic focus, honour flow, and reduce Autistic burnout.

In summary, polytropism explains how the neuromajority of people spread their attention widely across many things, while monotropic people channel their attention deeply into fewer channels, both are valid ways of being. By recognising and supporting everyone’s different attentional styles without judgment, we can move towards a neuroaffirming culture where everyone can thrive in their own unique ways.

Part 2 of this blog ‘Monotropic People in a Polytropic World‘ coming soon…..

A shorter version of this deeper dive is available here: Monotropism and Polytropism Explained

References & Further Reading

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Ashinoff, B. K., & Abu-Akel, A. (2021). Hyperfocus: The forgotten frontier of attention. Psychological Research, 85(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-019-01245-8

Basten, I. (2023). ADHD and attention: Rethinking intensity and variability. In H. Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, L. Hultman, S. Ö. Wiklund, A. Nygren, P. Storm, & G. Sandberg (Eds.), Intensity and variable attention: Counter narrating ADHD, from ADHD deficits to ADHD difference. The British Journal of Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad138

Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H., Hultman, L., Wiklund, S. Ö., Nygren, A., Storm, P., & Sandberg, G. (2023). Intensity and variable attention: Counter narrating ADHD, from ADHD deficits to ADHD difference. The British Journal of Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad138

Buckle, K. L., Leadbitter, K., Poliakoff, E., & Gowen, E. (2021). “No way out except from external intervention”: First-hand accounts of autistic inertia. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 631596. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631596

Collignon, O., Charbonneau, G., Peters, F., Nassim, M., Lassonde, M., Lepore, F., Mottron, L., & Bertone, A. (2013). Reduced multisensory facilitation in persons with autism. Cortex, 49(6), 1704–1710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2012.06.001

Craig, F., Margari, F., Legrottaglie, A. R., Palumbi, R., de Giambattista, C., & Margari, L. (2016). A review of executive function deficits in autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 1191–1202. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S104620

Craddock, E. (2025). Navigating residual diagnostic categories: The lived experiences of women diagnosed with autism and ADHD in adulthood. Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634593251336163

Garau, V., Murray, A., Woods, R., Chown, N., Hallett, S., Murray, F., Wood, R., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2023). Development and validation of a novel self-report measure of monotropism in autistic and non-autistic people: The Monotropism Questionnaire. Autism. Advance online publication.

Goldstein, G., Johnson, C. R., & Minshew, N. J. (2001). Attentional processes in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(4), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010620820786

Grotewiel, M. M., Crenshaw, M. E., Dorsey, A., & Street, E. (2022). Experiences of hyperfocus and flow in college students with and without Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Current Psychology, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02539-0

Heasman, B. et al., (2024). Towards autistic flow theory: A non‐pathologising conceptual approach. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 54(4), 623–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12445

Hossain, M., & Bain, S. (2025). Beyond behaviour: Understanding ADHD burnout and the need for belonging in UAE schools. Psychology in the Schools. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.70000

Hupfeld, K. E., Abagis, T. R., & Shah, P. (2019). Living “in the zone”: Hyperfocus in adult ADHD. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 11(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-019-00299-9

McDonnell, A., & Milton, D. (2014). Going with the flow: Reconsidering ‘repetitive behaviour’ through ‘flow states’. In G. Jones & E. Hurley (Eds.), Good Autism Practice: Autism, happiness and wellbeing (pp. 38–47). BILD.

Milton, D. E. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The ‘double empathy problem’. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Milton, D. E. (2014). Autistic expertise: A critical reflection on the production of knowledge in autism studies. Autism, 18(7), 794–802. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314525281

Milton, D. E. (2020). Monotropism: An interest-based account of autism. In F. R. Volkmar (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders (pp. 978–981). Springer.

Murray, F. (2023, October). Wellbeing [Keynote presentation]. Scottish Autism Research Group Conference, Edinburgh, Scotland. https://monotropism.org/wellbeing/

Murray, D., Lesser, M., & Lawson, W. (2005). Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for autism. Autism, 9(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361305051398

Raymaker, D. M., Teo, A. R., Steckler, N. A., Lentz, B., Scharer, M., Delos Santos, A., & Nicolaidis, C. (2020). “Having all of your internal resources exhausted beyond measure and being left with no clean-up crew”: Defining autistic burnout. Autism in Adulthood, 2(2), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2019.0079

Latest Posts

-

Autistic Burnout – Supporting Young People At Home & School

Autistic burnout in young people is real—and recovery starts with understanding. This post offers neuroaffirming ways to spot the signs, reduce demands, and truly support. 💛 #AutisticBurnout #Neuroaffirming #Monotropism #AutisticSupport

-

Monotropic Interests and Looping Thoughts

The theory of monotropism was developed by Murray, Lawson and Lesser in their article, Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for autism (2005). Monotropism is increasingly considered to be the underlying principle behind autism and is becoming more widely recognised, especially within autistic and neurodivergent communities. Fergus Murray, in their article Me and Monotropism:…

-

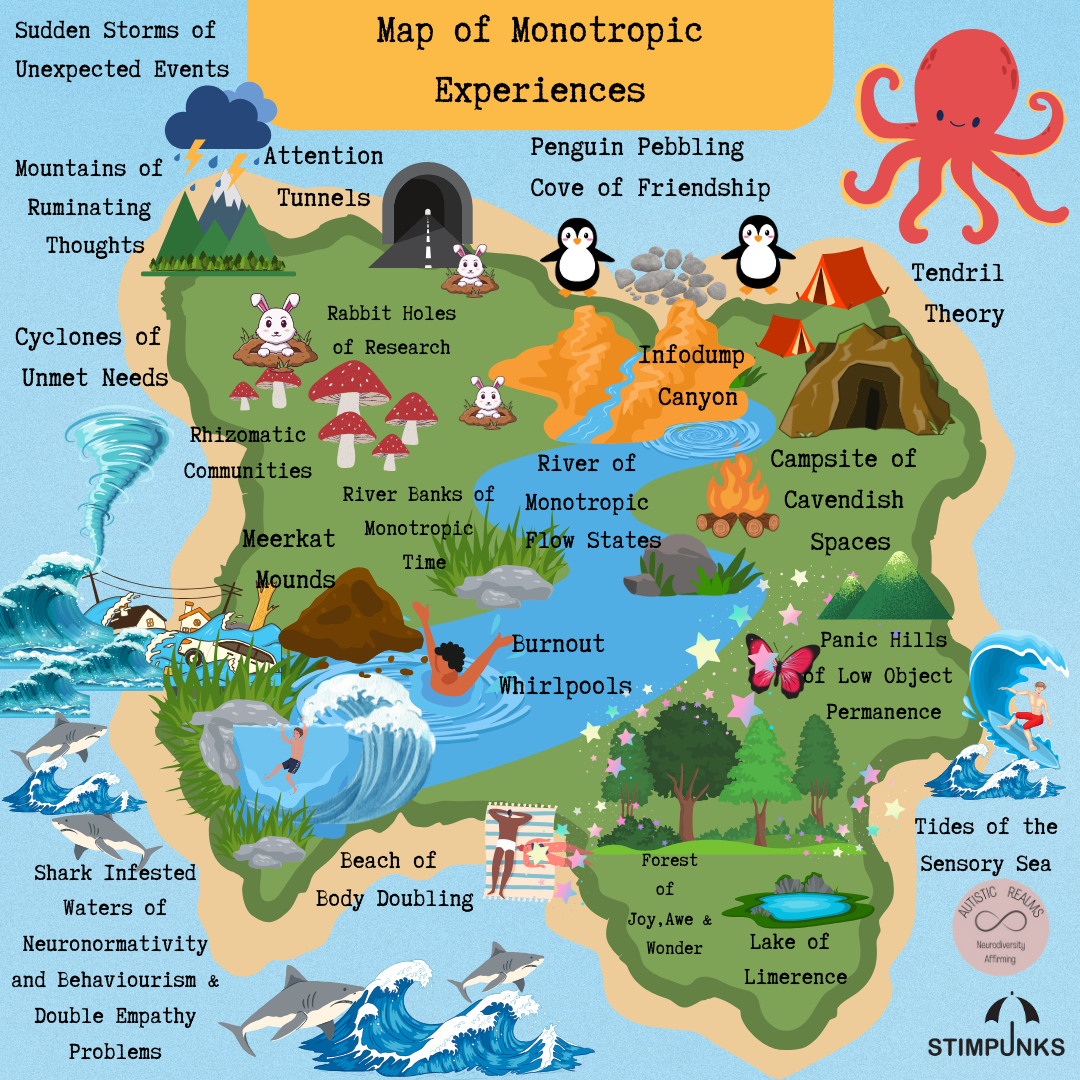

Map of Monotropic Experiences

Monotropism seeks to explain Autism in terms of attention distribution and interests. OSF Preprints | Development and Validation of a Novel Self-Report Measure of Monotropism in Autistic and Non-Autistic People: The Monotropism Questionnaire This map highlights 20 common aspects of my personal monotropic experiences. How many do you experience? Where are you on the map…

-

Autistic Burnout – Supporting Young People At Home & School

Being autistic is not an illness or a disorder in itself, but being autistic can have an impact on a person’s mental and physical health. This is due to the often unmet needs of living in a world that is generally designed for the well-being of people who are not autistic. In addition, three-quarters of…

-

The Double Empathy Problem is DEEP

“The growing cracks in the thin veneer of our “civilised” economic and social operating model are impossible to ignore”, Jorn Bettin (2021). The double empathy problem (Milton, 2012) creates a gap of disconnect experienced between people due to misunderstood shared lived experiences. It is “a breakdown in reciprocity and mutual understanding that can happen between people…

-

Top 5 Neurodivergent-Informed Strategies

Top 5 Neurodivergent-Informed Strategies By Helen Edgar, Autistic Realms, June 2024. 1. Be Kind Take time to listen and be with people in meaningful ways to help bridge the Double Empathy Problem (Milton, 2012). Be embodied and listen not only to people’s words but also to their bodies and sensory systems. Be responsive to people’s…

-

Autistic Community: Connections and Becoming

Everyone seeks connection in some way or another. Connections may look different for autistic people. In line with the motto from Anna Freud’s National Autism Trainer Programme (Acceptance, Belonging and Connection), creating a sense of acceptance and belonging is likely to be more meaningful for autistic people than putting pressure on them to try and…

-

Monotropism, Autism & OCD

This blog has been inspired by Dr Jeremy Shuman’s (PsyD) presentation, ‘Neurodiversity-Affirming OCD Care‘ (August 2023), available here. Exploring similarities and differences between Autistic and OCD monotropic flow states. Can attention tunnels freeze, and thoughts get stuck? Autism research is shifting; many people are moving away from the medical deficit model and seeing the value…

-

Monotropism Questionnaire & Inner Autistic/ADHD Experiences

Post first published 28th July 2023 Over the past few weeks, there has been a sudden surge of interest in the Monotropism Questionnaire (MQ), pre-print released in June 2023 in the research paper ‘Development and Validation of a Novel Self-Report Measure of Monotropism in Autistic and Non-Autistic People: The Monotropism Questionnaire.‘ by Garau, V., Murray,…

-

Penguin Pebbling: An Autistic Love Language

Penguin Pebbling is a neurodivergent way of showing you care, like sharing a meme or twig or pretty stone to say “I’m thinking of you,” inspired by penguins who gift pebbles to those they care about.

-

Discovering Belonging: Creating Neuro-Affirming Animations with Thriving Autistic

Discovering Belonging: Neuro-Affirming Animations with Thriving Autistic. Celebrate Autistic identity through the Discovery Programme and new animations that explore belonging, strengths, and community.

-

Being Autistic shapes grief: Explore unique paths through loss and affirming support

Explore how Autistic people experience grief differently and discover affirming resources, support, and strategies for navigating loss with compassion.

-

Reflections on the Autistic Mental Health Conference 2025

Reflections On The Autistic Mental Health Conference. An Interview between David Gray-Hammond & Helen Edgar