Written by Tanya Adkin and Helen Edgar, based on the presentation we delivered to the National Autistic Society Professionals’ Conference in March, 2025. Shared with permission from NAS.

We will explore the importance of the theory of monotropism and the significance of flow states and suggest some practical strategies educators can implement to create more inclusive, accommodating environments for Autistic students.

Embracing Neuro-Affirming Practices in Education

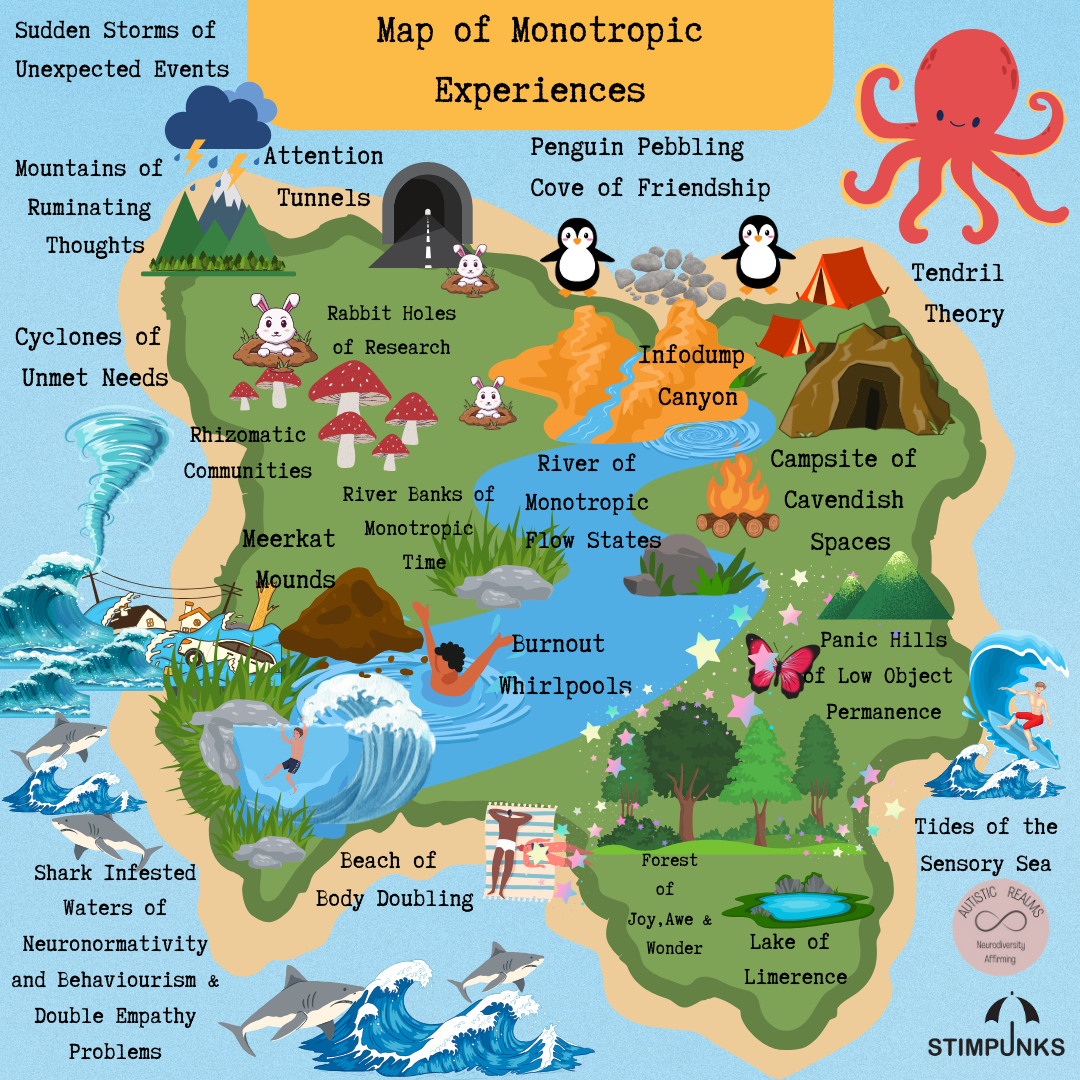

In today’s education system, supporting Autistic students effectively requires a shift away from outdated deficit-based models of Autism and a move towards a neuro-affirming approach. Understanding monotropism (Murray et al., 2005) is a great starting point. Monotropism is an Autistic-led and researched theory that explains how Autistic individuals process the world. There is increasing evidence that the theory of monotropism is also of benefit to ADHDers and also AuDHDers. Reframing how Autism is experienced from the lived experience of Autistic people is vital. It can be transformative for educators and professionals working with Autistic/ ADHD students to help meet their needs, help them feel better understood and help create a sense of belonging to support their well-being.

Challenges in Education: Why Change is Needed

Currently, educational systems are struggling to accommodate neurodivergent students, resulting in:

Increasing numbers of Education, Health, and Care Plans (EHCPs).

Higher rates of attendance difficulties.

Persistent reliance on deficit-based training models that fail to incorporate neuro-affirming perspectives.

Vast numbers of children and young people with unmet support needs.

Despite teachers’ dedication, most teacher training programs still promote outdated behaviourist approaches emphasising compliance over autonomy. This contributes to Autistic masking, burnout, and increased potential of long-term mental health struggles for Autistic students. This has broader implications for students’ parents/carers, family, and friendships.

Why the Neurodiversity Paradigm Matters

The neurodiversity paradigm shifts our understanding of Autism from a deficit-based model to a strength-based approach. Instead of aiming to “fix” neurodivergent individuals who do not need fixing, we must work toward adapting environments that respect and support their natural ways of thinking and learning. One way of doing this is to focus on the people we are supporting, really get to know them and meet them where they are instead of making assumptions about what we think Autistic people need. We need to be having conversations, listening to students, listening to parents/carers and listening to the stories and research shared by Autistic people – such as the theory of Monotropism.

Understanding Monotropism

Monotropism is a neuro-affirming theory of autism developed by Dinah Murray, Mike Lesser, and Wenn Lawson in the late 1990s. Their 2005 paper, Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for autism, explains how Autistic individuals process the world differently due to their deep, focused attention on fewer areas of interest at any one time.

Key Aspects of Monotropic Cognition:

● Deep Focus: Engaging deep flow states

● Difficulty Shifting Attention: Challenges in transitioning and splitting attention between activities/tasks/events/stimuli (Adkin, 2023)

● Intense Sensory Perception: The world is often experienced more profoundly

Honouring these natural cognitive processes rather than forcing neurodivergent individuals into neurotypical expectations can reduce stress, anxiety, overwhelm, burnout, and disengagement. By embracing people’s natural monotropic ways of being, we can help promote flow and intrinsic motivation and support the well-being of our students.

The Importance of Flow States

Flow states refer to deep engagement in a task. Everyone benefits from flow states, whether they are neurodivergent or neurotypical. Flow is essential for optimum learning environments, as it can lead to increased productivity and creativity. If it is ignited by something intrinsically motivating, it is often a joyful experience.

For monotropic individuals, flow states are critical to learning and regulation (Heasman et al., 2024), yet most school settings are not set up to embrace flow. Strict timetables, rigid curriculum agendas, demands for multi-tasking and frequent room changes and staffing can all significantly impact flow, which leads many Autistic people to suppress their authentic needs or find themselves in a state of cognitive and sensory overload. Students end up either masking or experiencing overwhelm (shutdown/meltdown) – either way, they are then unable to learn effectively. Supporting flow states through flexible learning approaches improves both educational outcomes and supports better mental health.

Creating Neuro-Affirming Environments and Pockets of Flow in the Classroom

To provide effective support for Autistic and ADHD monotropic students, we must shift our approach to align with neuro-affirming principles and also bear in mind how other neurodivergence may impact a person too (e.g. if they are also dyslexic, dyspraxic, etc.).

Increase Flow-Friendly Learning

● Allow flexible and more extended periods of deep focus when engaged in learning and intrinsically motivated.

● Avoid unnecessary transitions and interruptions.

● Provide autonomy in task selection and collaborate with the student (and their parents/carers when needed) to ensure their voice is heard and needs met. ● Be curious, and do not assume you know best about Autistic people – everyone is unique, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach.

Reduce Sensory and Cognitive Barriers

● Create adaptable sensory-friendly environments. Work with students and find out what they need; plan in advance but honour the fact that Autistic people have dynamic and fluctuating needs. What may work one day may not work the next.

● Implement low-demand engagement strategies – including the use of language. ● Allow stimming and movement as regulation tools – without restriction and stigma.

Rethink Transitions and Expectations

● Set up predictable yet flexible routines – ideally in collaboration with the young person.

● Allow extra processing and transition time when shifting tasks. This may mean a reduced timetable or curriculum or an extended curriculum for topics of greater interest.

Emphasise Strengths and Passions

● Integrate students’ interests into learning as much as possible to promote intrinsic motivation and flow states but ensure interests are not weaponised. Do not use an Autistic person’s interests and passions as part of a reward system to try to force them to conform to neurotypical expectations.

● Provide as many opportunities for self-directed study as possible.

● Encourage project-based and passion-driven education as much as possible to enable flow.

Train Educators in Neuro-Affirming Approaches

● Move away from behaviourist approaches.

● Centre, value, and believe in Autistic voices and research.

● Challenge outdated models of “functioning labels” and deficit-based language. ● Embrace neuro-affirming language and practice.

The Impact of Masking and Burnout

Many Autistic students mask their authentic selves to fit into neurotypical expectations. This leads to increased anxiety, exhaustion, and potential burnout; it can also impact attendance at school. Masking leads to a higher risk of mental health crises and also suicidality for Autistic students. A disconnection from their own authentic Autistic identity can seriously impact their well-being and lead to a poorer quality of life (Pearson & Rose, 2021).

Understanding the theory of monotropism and creating neuro-affirming environments can help promote flow and support well-being. A supportive, understanding and accommodating environment where differences are celebrated and difficulties supported will reduce the need for masking and increase a sense of Autistic pride and autonomy. We need to think about how we can create environments that promote well-being and autonomy rather than compliance, as Luke Beardon’s famous equation states:

Autism + Environment = Outcome (Beardon, 2022)

Reframing Language: The Power of Neuro-Affirming Terminology

When we talk about environments, we are not just talking about the physical layout of the school building and classroom. We also need to consider the wider environment and the relationships between teachers, students, and their families. We must consider differences in communication styles between Autistic and non-autistic people and the Double Empathy Problem (Milton, 2012). The way we communicate and the language we use shape perceptions. Shifting to neuro-affirming language helps create a culture of acceptance and respect. We suggest considering the following:

● Use identity-first language: “Autistic person” rather than “person with Autism”, as preferred by the majority of the Autistic community (Kenny et al., 2016) ● Avoid functioning labels such as profound Autism and high functioning: Instead, describe specific support needs (Kapp, 2023)

● Reframe Autism through the lens of monotropism: Replace “restricted interests” with “passions” and “being stuck on an activity” with “being in a flow state.” Consider how the impact of multiple stimuli and demands affects attention resources and can lead to overwhelm.

The Path to a Neuro-Affirming Future In Education

By meeting the needs of Autistic monotropic learners, you are also providing space and provision for everyone to benefit from a more accessible school environment and education. We need to allow flexible learning schedules and adapt environments for sensory and emotional regulation to allow pockets of flow through the day. We need to build trust through affirming relationships by listening and collaborating with neurodivergent students and their families to ensure their needs are met and they feel safe, understood and supported.

By shifting our educational practices to honour monotropic ways of being and embracing neurodiversity, we can help to create environments where all students thrive rather than Autistic students just trying to survive and ending up being burned out. The goal is to build a system that values, respects and nurtures neurodivergent minds. Let’s move beyond outdated models and embrace true inclusion and equity through neuro-affirming practice—because when we get it right for neurodivergent and monotropic individuals, we get it right for everyone.

References & Related Reading

Adkin, T. (2023, October 13). Guest Post: What is monotropic split? – Emergent Divergence. Emergent Divergence.

Arnold, S. R., Higgins, J. M., Weise, J., Desai, A., Pellicano, E., & Trollor, J. N. (2023). Confirming the nature of autistic burnout. Autism, 27(7), 1906–1918.

Beardon, L. (2022). What works for autistic children. Sheldon Press

Dwyer, P., Williams, Z. J., Lawson, W. B., & Rivera, S. M. (2024). A trans-diagnostic investigation of attention, hyper-focus, and monotropism in autism, attention dysregulation, hyperactivity development, and the general population. Neurodiversity, 2.

Edgar, H. (2023a September 7). Embracing autistic children’s monotropic flow states — neurodiverse connection. Neurodiverse Connection.

Edgar, H. [Autistic Realms]. (2023b, September 27). Supporting your young person through autistic burnout. THINKING PERSON’S GUIDE TO AUTISM.

Garau, V., Woods, R., Chown, N., Hallett, S., Murray, F., Wood, R., Murray, A. L., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2023). The Monotropism questionnaire. OSF.

Heasman, B., Williams, G., Charura, D., Hamilton, L. G., Milton, D., & Murray, F. (2024b). Towards autistic flow theory: A non‐pathologising conceptual approach. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour.

Kapp, S. K. (2023). Profound Concerns about “Profound Autism”: Dangers of Severity Scales and Functioning Labels for Support Needs. Education Sciences, 13(2), 106.

Keer, M. (2024, July 24). Depressingly awful data and our 2024 EHCP Hall of Shame reveal the sad state of disabled children’s education, with growing numbers out of school. Special Needs Jungle.

Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., & Pellicano, E. (2015). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442–462.

Lawson, W. (2010.). The passionate mind. Jessica Kingsley Publishers UK

Milton, D. E. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: the ‘double empathy problem.’ Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887.

Murray, D., Lesser, M., & Lawson, W. (2005). Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for autism. Autism, 9(2), 139–156.

Murray, F. (2018). Me and Monotropism: A unified theory of autism. BPS.

Murray, F. (2023, September 4). Theories and Practice in Autism – Medium.

Pearson, A., & Rose, K. (2021). A Conceptual analysis of Autistic Masking: Understanding the narrative of stigma and the illusion of choice. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 52–60.

Phung, J., Penner, M., Pirlot, C., & Welch, C. (2021). What I wish you knew: Insights on burnout, inertia, meltdown, and shutdown from autistic youth. Frontiers in Psychology, 12.

Shepherd, J., Sutton, B., Smith, S., & Szlenkier, M. (2024). ‘Sea‐glass survivors’: Autistic testimonies about education experiences. British Journal of Special Education, 51(2), 142–155.

Wood, R. (2019). Inclusive education for autistic children: Helping Children and Young People to Learn and Flourish in the Classroom. Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Signposting

Monotropism.org the official website about all things monotropism related, hosted by Fergus Murray

Helen Edgar’s website, Autistic Realms

Helen Edgar’s Booklet: Embracing Monotropism and Supporting Young People To Help Prevent Autistic

David Gray-Hammon’s website, Emergent Divergence

Wenn Lawson’s website, Build Something Positive