The phrase we must “presume competence” has become a kind of mantra in inclusive education and disability discourse. Its roots lie in the Least Dangerous Assumption principle (Donnellan, 1984), if we are unsure about a person’s abilities, it can be seen to be far less harmful to assume they do understand and “can do” than to assume they do not understand and “can’t do”. However, presuming competence isn’t inherently good, it doesn’t just mean cognitive and intellectual abilities. It depends on many factors, supports and we need a more nuanced approach.

Autistic people have spent decades being underestimated, doubted, excluded from meaningful learning, and spoken over because our communication, ways of moving, and ways we process our attention and sensory systems are different. Presuming competence in a neuro-affirming way allows space for our inner worlds, how we think, we know, we feel, and how we have agency, even if we express it differently.

However, if presuming competence is applied without nuance and without adopting a neuro-affirming approach it becomes a potentially harmful ableist assumption based on neuronormative values. With out additional supports “presuming competence” can be more harmful than helpful.

If we always presume competence for those we are with, especially Autistic people with learning or intellectual disabilities without the right support and sensory and communication accomodations in place, we are setting them up to fail. In addition if those people also have other physical or medical needs and are not feeling safe or comfortable in their own bodies then there are other barriers that need addressing too.

Joanna Grace captures this clearly in her critique of over-applied presumption of competence when supporting those with Profound and Multiple Learning Disablities for SEN Magazine (A Dangerous Assumption, 2019):

“People assuming I am like them

does me harm.”

“A narrative of aiming high does these children [with PMLD] no favours.”

(Grace, J., (2019). SEN Magazine, A Dangerous Assumption?)

On whose terms?

Presuming competence is empowering only when it is accompanied by the right supports. When “I believe you can” becomes “now prove it, on my terms,” the result isn’t inclusion, it’s pressure to conform, mask and adapt. It impacts a person’s well-being and can leave them fighting in survival mode. We need to take time to meet people where they are, be present, get to know them, help them feel safe.

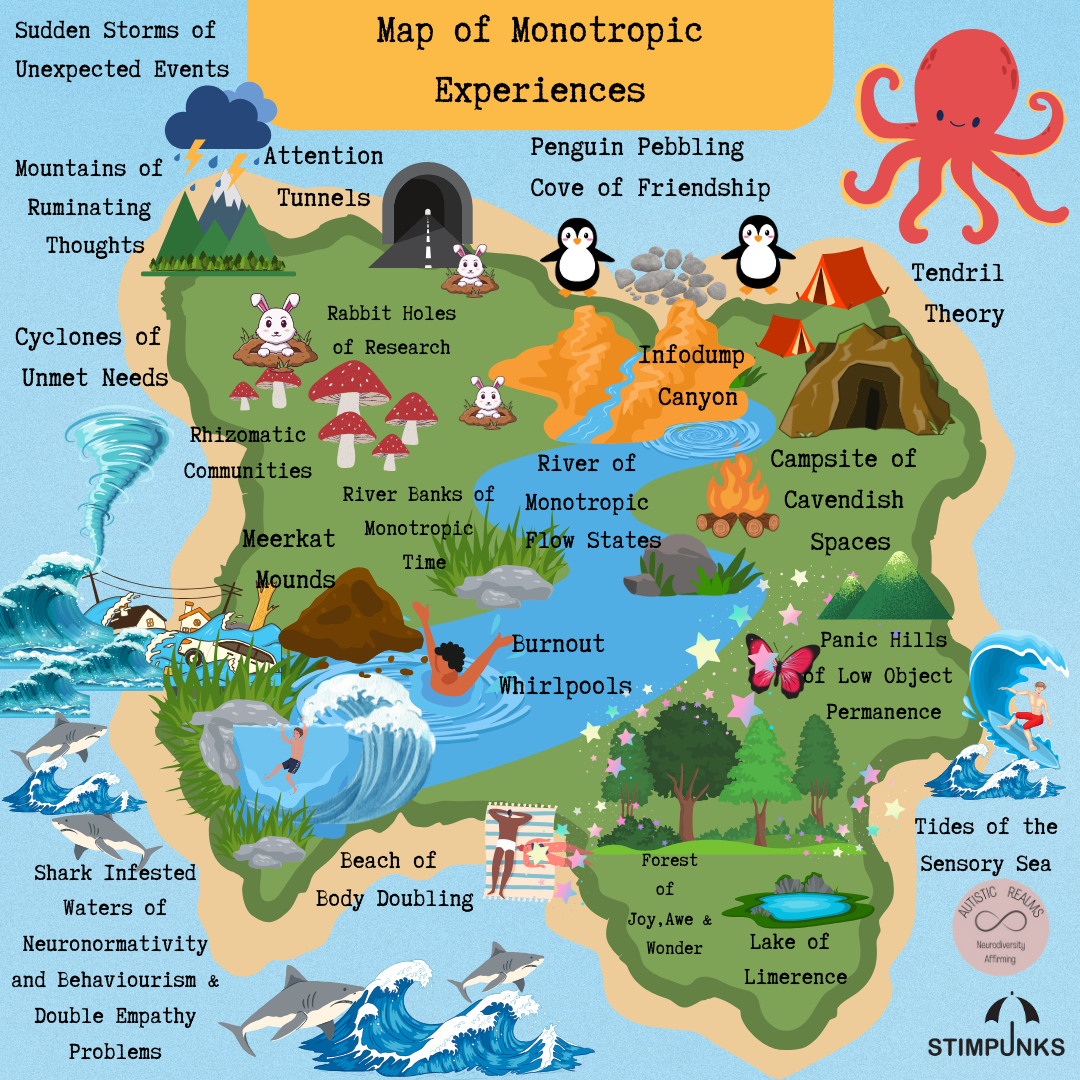

For example, for many Autistic people, communication is filtered through sensory load, emotional regulation, processing time, and monotropic attention. People who are able to use their voice to communicate may struggle more under stress or in unsupportive environments and may not be able to speak at all in these times. Expression may emerge through movement, text, scripting, or silence. If someone presumes competence and still expects eloquent speech, constant responsiveness, and multi-person interaction, they are not honouring our competence; they are ignoring our Autistic needs and authentic ways of being. On the other side of this coin, if a person is non or minimally speaking then incompetence may be presumed, which is also deeply problematic.

This is where presuming competence can morph into performative inclusion, which is a belief that everyone can or should be able to perform, even without support. A teacher might insist on “high expectations” without AAC in place and without enabling access to the right sensory tools and any awareness or consideration of the energy and capacity a person may have in that moment.

Teachers or therapists may assume people’s skills can be generalised because they once appeared in a specific context, not taking into account neurodivergent spiky profiles and the potential overlapping consequences of a person’s multiple neurodivergent needs and other factors such as their medical or health care needs. A family member or colleague might interpret a shutdown or state of overwhelm as refusal, rather than thinking about a person’s capacity is being pushed passed their limits into cognitive, sensory and social exhaustion.

Grace challenges us to reflect on the bias beneath all of this:

“Are your ‘high expectations’ actually a front for a prejudice hidden in you that says to be cognitively disabled is terrible?”

If presuming competence means expecting Autistic people to behave more in a more neuroconformist way, then it is no longer about respect; it is about assimilation and is ableist. We need neurodivergent competency, as Adkin and Gray-Hammond write in Creating Autistic Suffering: Autistic safety and neurodivergence competency (2023).

“Competency cannot exist without safety, and safety cannot exist without competency. In the context of Autistic safety, one must have neurodivergent competency. A person having knowledge of their own experience and having the understanding and language to advocate for themselves increases safety. This cannot be taught without competency.”

Creating Autistic Suffering: Autistic safety and neurodivergence competency (Adkin and Gray-Hammond, 2023)

Being competent means more than having awareness, it means recognising Autistic experiences as valid, taking responsibility for creating environments of safety and respect, and working to ensure Autistic people are able to thrive rather than face further trauma.

A Relational Stance

Presuming competence must be a relational stance, not a performative demand. We need to be with people, adapt environments, meet sensory needs, expand communication access, offer more processing time for our monotropic needs, offer interest-led learning for our children and treat each person’s ways of showing understanding and expressing themselves as valid and real. We need safe spaces, co-regulation and to understand that inter-dependence is valid.

“Value each life as it is.

Value the hours within it.

Value the skills already present.

Measure against measures meaningful to the person.”

Presuming neurodivergent competence isn’t about what we think could be unlocked in the future but about honouring what exists now, in forms and ways we may not yet recognise. We need to really tune in, lower demands, be with people, and allow them the safety to be themselves.

Autistic-led scholarship emphasises that presuming competence must be grounded in the neurodiversity paradigm, recognising Autistic cognition as valid rather than assessing it against neurotypical norms (Botha et al., 2021; Milton, 2012). Milton’s Double Empathy Problem highlights that misunderstandings arise between people based on their experiences—not from Autistic deficit—which means competence can only be recognised within relational, respectful contexts and that it is a two way process.

Pearson and Rose (2021) further demonstrate how masking and social survival strategies can hide Autistic distress and needs beneath a performance of competence, meaning “high expectations” can contribute to exhaustion, minority stress, and burnout if safety and access needs are not prioritised. Together, these insights make a really clear point that presuming competence is not about demanding neurotypical displays and ways of being, but that we must reduce systemic barriers so our Autistic ways of being are better understood, accepted and supported.

“In a world of high expectations we need to be absolutely sure that the measures we choose are chosen in a child centred way, and not placed there by edicts from on high or influenced by generalised assumptions of what is best for everyone.”

Final Thoughts…

Everyone is capable of expressing love and communicating in their own way. We need to presume competence responsibly, ethically, and within a neuro-affirming framework. We are all human trying to thrive (not just survive) in a very ableist society. We need kindness, compassion and understanding.

Presuming neurodivergent competency must prioritise belonging, not productivity, and needs to be grounded in the lived realities of Autistic experiences, not in neuronormative fantasies of independence always being the best or right way to live.

We can support Autistic people by:

- respecting Autistic communication and social differences

- supporting access before expecting demonstration or performance

- recognising fluctuations of energy, sensory differences and spiky profiles

- allowing competence to emerge in authentic Autistic ways

- taking into account intersectionality and how that may impact some one

- creating emotional, psychological, sensory and cognitive safe spaces

- embracing the theory of monotropism and allowing time for flow, interest-led person centred led-learning

- being needs led – not focusing on labels or diagnosis

- embracing inter-dependence

When “presume competence” is applied without a neuro-affirming lens, it can become a harmful, ableist expectation. Presuming competence isn’t about demanding compliance, we need to embrace a neuro-affirming approach.

https://stimpunks.org/learning/respectful-connection

Further reading:

https://timetolisten.blogspot.com/2013/07/presuming-competence-not-just-about.html