Practising Curiosity, and “Being With” in Care and Education Through the SPACE Framework

*NB this is my own personal reframing and ideas inspired by the Autistic Space Framework and research of Doherty et al (2023) & McGoldrick et al (2025), I am not in any way affiliated**

Children and people described as having Profound and Multiple Learning Disabilities (PMLD) and “complex needs” are often supported within systems shaped by deficit-based models, and pressure to move people towards neuronormative goals. Professional training has traditionally emphasised standardisation, skill acquisition, and compliance with normatively defined outcomes. As a result, children’s lives are frequently understood through what they cannot do, the care they require, and the targets they have not met, rather than through how they really may be experiencing the world, communicating, what they need to regulate, and how they form relationships and create meaning.

For many children with PMLD, this framing also obscures the central role of their identity, physical comfort, health, medical vulnerability, and access to consistent care in shaping how they experience the world and engage with others. Pain, fatigue, communication differences, feeding difficulties, respiratory challenges, epilepsy, physio, positioning needs, sensory sensitivities and many other factors are often treated as separate issues, rather than being seen as a whole, and this can fragment their sense of identity and impact their well-being.

Embodied Ways of Knowing

Even as neurodiversity-affirming language becomes more common across education, therapy, and healthcare, care and support needs for children with PMLD often remains rooted in what can be described as “neurodiversity-lite”: a surface shift in terminology, such as moving from “non-verbal” to “non or minimally speaking”, without a deeper shift in values and recognising power dynamics and truly valuing people as they are. Children may be spoken about in neurodiversity-positive ways, yet still positioned as objects of intervention, expected to adapt to systems built around typical development, behaviourist-oriented goals, and neuronormative-led timescales.

This can leave a child’s identity, agency, and embodied ways of knowing marginalised or even totally dismissed, and can pull professionals back into working and doing assessments on children rather than with them, even when intentions are compassionate and well-meaning. In such systems, healthcare, physical support, emotional wellbeing, and learning are often treated as separate domains, rather than as deeply interconnected aspects of everyday life.

Neurodiversity Paradigm

The neurodiversity paradigm as described by Nick Walker (2021), invites a fundamental change. It recognises difference as part of natural human variation and places safety and interdependence, rather than independence, at the heart of development and wellbeing. From this perspective, children with PMLD are not defined by what they cannot do, but are understood as relational, sensing, and embodied beings whose communication and sense-making are expressed through movement, sensation, rhythm, affect, shared co-regulation and interdependence.

We need to recognise that access to education and healthcare has many barriers for those who may also be multiply marginalised by race, gender and other factors. Reliable support is foundational to safety, regulation, and participation. Many children with PMLD live with significant physical and health care needs in addition to their learning disabilities and may rely on specialist equipment, personal care, therapy input, medication, and consistent support in order to be comfortable, regulated, and well. All of this is usually negotiated and managed by exhausted family members on their behalf, involving large teams of people, often with the best of intentions, but also often speaking for the child or family without really taking the time to get to know them and truly hear their voices (however they may be expressed).

Meaning is not something to be extracted or decoded by professionals from people when doing observations and assessments on them. It should be something that needs to be co-created over time, within safe relationships and environments, on the child’s terms. Relationships built through careful attention to bodily comfort, sensory access, and emotional safety, alongside access to people who understand their ways of communicating and connecting, enable the most vulnerable people to truly be active participants in their own care and learning plans.

The SPACE Framework

The Autistic SPACE framework began as a profoundly humanising model to improve access and experience for Autistic people in healthcare settings, highlighting five interrelated domains that support wellbeing and participation: Sensory needs, Predictability, Acceptance, Communication and Empathy, with an underlying foundation of an understanding of physical, processing and emotional differences and needs.

Originally developed by Doherty, McCowan and Shaw (2023) to address barriers to equitable health care and promote environments where Autistic experiences are better understood so their authentic needs can be met, this framework emphasises dignity, respect, and shared understanding rather than correction or compliance. Building on this foundation, McGoldrick, McCowan, and Shaw (2025) expanded and adapted it to create the paper, “Autistic SPACE for Inclusive Education.” This extends its principles into educational settings by helping professionals think beyond deficit-based models and supporting them in creating learning environments that truly accept and attend to how Autistic children experience sensory input, predictability, communication, and build connection and safety, which are the foundations for learning effectively.

Such a shift requires a process of unlearning as well as learning for those supporting children. It involves questioning inherited frameworks that prioritise standardisation, neuronormative expectations, and adult-led goals, and relearning through a neuroaffirming, relational, and child-led paradigm instead. This means slowing down, attending more carefully to children’s embodied, sensory, and emotional worlds, having empathy and developing a shared understanding over time.

While the health care and educational SPACE frameworks were developed with Autistic people in mind, I think their core values remain deeply humanising and can be equally as valuable for those with PMLD. By foregrounding safety, relational attunement, and meaningful participation, the framework offers a way of supporting all people, including those with profound and multiple learning disabilities (PMLD), whether or not they are Autistic, in ways that make sense for their embodied, sensory lives and different ways of experiencing and being in the world.

Neuroaffirming assessment, guided by the SPACE Framework, is not about capturing a child’s “performance” or needs within a brief observation window. It is about creating Sensory-safe, Predictable, Accessible, Collaborative, and Empathic spaces in which a child or young person can gradually feel secure enough to show who they are.

This means spending unhurried time with the child, following their lead, noticing their interests, strengths, and learning with them to discover their unique sensory, emotional, and communication rhythms. It involves developing shared understanding through trust, attunement, and reciprocity and responsiveness rather than through checklists and snapshots.

The SPACE Framework supports a slower, more dynamic process grounded in curiosity and openness. It encourages practitioners to attend carefully to how health, fatigue, pain, positioning, medication effects, and sensory needs and the environment can shape engagement, regulation, and identity over time. Rather than asking how well a child can perform, it asks how environments and relationships can be co-created so that the child can participate authentically and feel safe. In this way, the SPACE Framework helps us shift assessment and observation from extraction to relationship, from judgment to understanding, and from compliance to genuine, meaningful connection and creating a shared sense of belonging.

Curiosity And Empathy Gaps

Central to this shift is a different way of thinking about “presuming competence.” Instead of assuming that children are thinking and understanding in typical ways that are simply hidden from view or not accessible, this approach starts from the belief that every child is already making sense of the world in their own way and able to express themselves in some way.

Every child is a meaning-maker. Meaning is not something that only exists in words, symbols, or behaviours that fit typical developmental expectations — it lives in our bodyminds, in our rhythms, in sensations, in emotional expression, in posture, in eye contact (or its avoidance), in shifts of breath, in changes in tone, in quiet stillness, in movement, in affective engagement and withdrawal, and in the subtle ways we respond to one another and the spaces we are in. Our bodies are always communicating; before language develops as we resonate with others and respond to our environment. We all express our experiences through our whole ways of being and this is even more important to understand when being with and supporting those with PMLD.

For children with PMLD, and for many who communicate in ways that differ from the spoken or written norm, this means that every gesture or vocalisation or body movement, no matter how small can carry significance. A change in muscle tension, a shift in gaze, a moment of calm, a turn towards a familiar voice or scent, a shared breath: all of these can be meaning-laden, expressing joy, pain, engagement or disinterest. Assuming that children who do not use conventional language lack inner life, emotion, or communicative intent is not only incorrect, it is deeply limiting and dehumanising.

This understanding echoes Joanna Grace’s (2019) challenge to the “dangerous assumption” the implicit belief that children with PMLD lack inner life, emotional depth, or subjectivity simply because their ways of communicating do not align with neurotypical norms. Grace urges us to honour presence before performance, and experience before conformity. She encourages us to recognise that every person, regardless of how they communicate or move through the world, has a rich inner life, personal preferences and their own emotional sensory landscapes. To honour this is to understand the full range of human expression, including the embodied, sensory, affective, and relational ways that children with PMLD make meaning and sense of their lives.

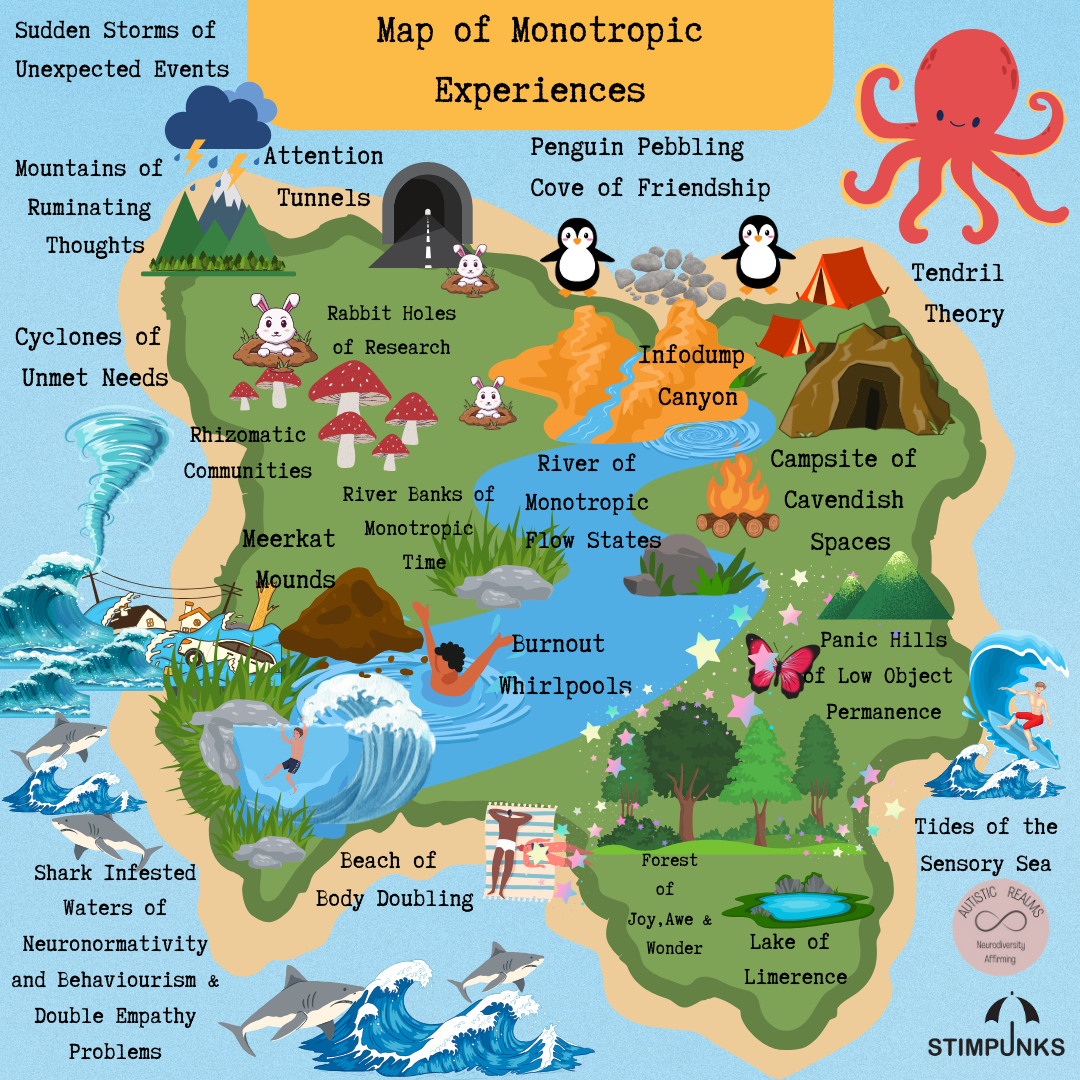

An understanding of this can be further deepened by exploring the impact of the double and triple empathy dynamics. From a double empathy gap perspective (Milton, 2012), difficulties in understanding often arise in the space between people with different sensory, communicative, and meaning-making worlds, rather than being located within the child. For those with PMLD and their families, this is often intensified into a “triple empathy” gap (Shaw et al., 2023), in which children’s embodied communication and families’ relational knowledge are filtered through professional languages, assessment frameworks, and institutional timescales that only privilege certain forms of evidence and expression. Children’s experiences of pain, discomfort, illness, and bodily vulnerability are often filtered through these frameworks that privilege certain forms of evidence over lived experience. Families’ interpretations of how health and wellbeing shape communication may be questioned, marginalised or discounted, or at worst, they can be blamed.

Working neuroaffirmatively involves sharing power, co-constructing meaning, valuing lived knowledge as a legitimate form of evidence, and, more importantly, spending quality time WITH the children and families, on their timescale.

How The SPACE Framework May Support Those With PMLD

The SPACE Framework (Doherty et al., 2023 & McGoldrick et al., 2025) can be understood as an ethical and attunement-based orientation for not only supporting Autistic people, but perhaps also children and people with PMLD by becoming more responsive to their sensory, emotional, and relational worlds:

- Sensory attunement – recognising the child’s sensory experiences as a primary mode of meaning-making and the importance of the environment to meet needs

- Predictability and emotional safety – valuing temporal, relational, and bodily needs as foundations for regulation and trust with others

- Acceptance and presuming meaning – approaching expressions, behaviours, and bodily movements as meaningful, without translating them into deficit or measuring them against normative developmental expectations.

- Communication – understanding communication as an embodied and often a sensory relational process

- Empathy – recognising that difficulties in understanding often arise when people are experiencing the world in very different ways, and when those differences are not fully recognised or respected.

This framework aligns with neuro-affirming practice and is a move away from “doing-to”, towards “being-with”: prioritising presence, pacing, curiosity, and shared regulation over performance, targets, and behavioural compliance.

This shift requires explicit attention to relational ethics, bodily autonomy, and consent. For children whose communication may be primarily sensory and may have limited understanding or use of language or AAC devices, consent is an ongoing, embodied, relational process. A neuroaffirming, trauma-informed stance involves attending carefully to the child’s cues of comfort, joy, withdrawal, interest, and distress, and shaping practice around safety, predictability, and respectful touch, positioning the child as an active participant in processes rather than a passive recipient of care. This includes careful attention to how medical care, positioning, physical support and personal hygiene needs are experienced.

Taken together, these perspectives offer a neuroaffirming framework for understanding and supporting children with PMLD. They integrate the neurodiversity paradigm, trauma-informed and ethically grounded care, double and triple empathy, and adaptations of the SPACE Framework.

They support a move away from deficit, compliance, and normalisation, and towards curiosity, co-regulation, shared meaning-making, and being-with rather than doing-to; meeting children with PMLD where they are at as sensing, feeling, communicating people whose ways of knowing are embodied and already meaningful.

Rethinking Progress

Rethinking what progress means and looks like is a key part of this paradigm shift. For children with PMLD, thriving is best understood not as linear movement towards normative developmental milestones, but as a rhizomatic, interconnected process of growing safety, trust, regulation, comfort, communicative agency, pleasure, curiosity, and engagement in ways that make sense for them. This includes access to interests that bring joy and sensory pleasure.

Progress may also be reflected in improved physical comfort, better-managed health needs, increased trust in caregivers, and more consistent access to appropriate support, all of which are the foundations to being regulated enough to engage and learn. Goals shouldn’t be imposed in advance; they need to emerge from the child’s rhythms, interests, sensory needs, and from what supports them in feeling secure and connected within their everyday environments and relationships. This isn’t about not believing in their potential or about not moving forward in their education; rather, it is about ensuring children are co-leading and are part of the process and plan for shaping their own lives.

If this shift towards neuroaffirming, relational practice is to be more than an individual commitment, it must be supported structurally and systemically. Settings and commissioning bodies need to invest in time for relationship-building, reflection, and shared learning. This includes reducing unmanageable caseloads and instead funding roles that support continuity and value specialist expertise in embodied, sensory, and trauma-informed practice. It also means protecting space for reflective supervision, interdisciplinary collaboration, and ongoing professional learning that centres lived experience. Meaningful change, therefore, depends not only on individuals but also on organisational cultures and policies that resource interdependence, care, and sustained presence, and that reframe and embrace neurodiversity affirming practice.

Moving beyond “complex needs” does not mean minimising support. It means recognising that thriving is always relational and grounded in practices of being with rather than managing or fixing. It depends on reliable healthcare, skilled and reflective staff, accessible, safe environments, sustained relationships, and systems that value time, attunement, presence, and quality care. Children with PMLD are not “problems to be solved” or “managed”, but sensing, feeling, communicating people whose ways of knowing and being are already meaningful, if we tune in.

Honouring this requires not less support, but better more informed affirming support. Not greater pressure towards independence, but deeper commitment to interdependence. We don’t need faster pathways and tighter targets; instead, we need slower, more ethical, and more responsive ways of being with and alongside children in their everyday lives. We need to listen, learn, and be responsive so we can build relationships grounded in trust, respect, and shared experiences, enabling children to feel safe to learn and support their well-being.

This is about reclaiming education, healthcare, and support as relational, ethical, and human practices. Through approaches such as the SPACE Framework and being with children in their embodied, sensory, and emotional worlds, we are invited to resist deficit-based systems and to build cultures of care rooted in dignity and trust.

Moving beyond “complex needs” means committing to a deeper presence, deeper listening, and deeper responsibility. It means choosing to be with children on their own terms, spending quality time with them, meeting them where they are in each moment, and learning from their ways of being in the world. It means valuing children as unique individuals and honouring their rich inner sensory lives, their ways of communicating, and their right to be known, respected, and supported so that they can feel safe and secure in their own ways.

This calls for relational presence: showing up with attentiveness, patience, and openness, and being willing to stay alongside and with children without rushing, fixing, or controlling them. By being truly present, curious, and kind, we can help create environments where children with PMLD are not only supported but are genuinely seen, valued, and loved for who they are, so they feel safer and can live, learn, and belong and flourish on their own terms.

References & Further Reading

Cherry, L. (2026, January 19). Part one – Trauma Informed practice as the new tick box. Dr Lisa Cherry. https://drlisacherry.substack.com/p/part-one-trauma-informed-practice?r=32h7ol&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&triedRedirect=true

Doherty, M., McCowan, S., & Shaw, S. C. K. (2023). Autistic SPACE: A novel framework for meeting the needs of autistic people in healthcare settings. Journal of Health Management. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2023.0006

Edgar, H. (2025). Beyond neurodiversity-lite: Why authentic neurodiversity-affirming practice matters. Autistic Realms. https://autisticrealms.com/authentic-neurodiversity-affirming-practice-matters/

Gorski, P. (2021) How Trauma-Informed are we, really?. ASCD. https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/how-trauma-informed-are-we-really

Grace, J. (2019). A dangerous assumption. SEN Magazine.https://senmagazine.co.uk/content/specific-needs/pmld/20657/a-dangerous-assumption/

McGoldrick, E., Munroe, A., Ferguson, R., Byrne, C., & Doherty, M. (2025). Autistic SPACE for Inclusive Education. Neurodiversity, 3. https://doi.org/10.1177/27546330251370655 (Original work published 2025)

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The “double empathy problem”. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887.https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Shaw, S. C. K., Carravallah, L., Johnson, M., O’Sullivan, J., Chown, N., Neilson, S., & Doherty, M. (2023). Barriers to healthcare and a ‘triple empathy problem’ may lead to adverse outcomes for autistic adults: A qualitative study. Autism.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37846479/

Walker, N. (2021). Neuroqueer heresies: Notes on the Neurodiversity Paradigm, Autistic Empowerment, and Postnormal Possibilities. Autonomous Press.